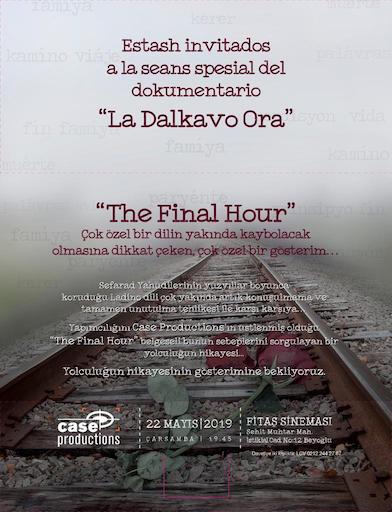

La Dalkavo Ora (The Final Hour)

The film La Dalkavo Ora, which depicts the centuries-long journey of a Sephardic family, serves as a document that will be passed on to next generations. While watching the film, you set off from Istanbul and travel to first Greece and then to Auschwitz, Portugal and finally to Spain where everything had started. We talked with Producer Selim Kemahli, Director Caglar Malli, actress Deniz Bensusan and composer Renan Koen about the story of how the film was made.

How did you decide to make La Dalkavo Ora, a documentary about Ladino?

Selim: My grandmother’s mother lived until she was 100. She was a member of the palace and she spoke Turkish in a different dialect. She grew up during the Ottoman Period. Then came the Republican era and the alphabet changed. She adapted to the new alphabet. I was serving in the military when she passed away. That’s when I realized that it was the end of an era. With that generation gone, I knew that those people who personally witnessed that change, were no longer able to share their first-hand experiences with younger generations. I felt resentment for not asking my great grandmother more questions about those times and for not taking any notes. Those stories could no longer be told. They faded away together with her. The subject of Ladino was always on my mind. When I looked at my elementary school yearbook, half the school were non-Muslims. You are not aware of it when you are a child, but when you look back now, you see that there was a very different demographic back then. I grew up in Yenikoy. In the summers we used to go to Buyukada (Princess Island). There was a certain culture and that culture started to fade away. When the topic of filming a documentary came up, I told my partner Cem (Kitapci) “Let’s do this subject or it will be too late, and we’ll never be able to do it again.” I find it very interesting. There is this language; there are still people speaking this language, yet the new generation won’t speak it. When grandparents who speak that language are gone, that language along with its unique culture will be gone, too.

One character accompanies us during the film and in a way her family’s story steers the film. How did you meet Deniz Bensusan?

Selim: When we decided to build the story on a character, we put an ad on Salom Newspaper indicating the specific qualifications we were looking for. We interviewed several candidates and decided to go with Deniz. Her family’s story was intriguing.

Deniz Bensusan: My family’s story fits right into Ladino’s most common course. In the Ottoman period, my grandfather who was a tobacco expert, moved first to Edirne with his family and then from Edirne to Istanbul. During the filming, it was interesting to find my cousin in Greece.

How did you develop the story?

Caglar Malli: Before we started filming, we first went to Spain, Portugal, Greece, and Poland. We visited several locations. We found the relevant people and got the necessary permits. Every place you go, you learn something new, so I can say that the story was developed organically. We made sure that the language remained as the backbone of the story throughout the whole film, but we also mentioned secondary topics. After reviewing the materials we collected, we decided that it would be better to approach the theme from a cultural point of view, rather than solely focusing on the language.

What were the biggest challenges you experienced during the whole process?

Selim: Throughout the whole filming process we looked for financial support, we are still looking. Since we are not members of the Jewish Community, the community was apprehensive about the film we were making, and I find this very normal. In Thessaloniki we were not allowed access to the archives and in Porto we were now allowed access to the Synagogue. We also worked really hard to get a filming permit inside Buyukada Synagogue.

Renan, how did this film make you feel? How did it affect your music?

Renan Koen: Besides being emotionally affected by my own family’s course of exodus, I am also deeply touched by the course Sephardic people took, after being expelled from Spain. Everywhere they went, they brought their own culture, their own music, their own regional terminology and all other elements that make them unique, with them. This is very touching and precious. Sephardic people have come to this day through multiplying in an ocean of various geographies. Exploring this wealth, living in it and reflecting it really touches me.

Deniz, how did your mother and grandmother feel when they told their family’s story in the documentary?

Deniz: My grandmother has never wanted to talk much about the traumatic parts of her family’s story. She still tears up when she talks about it. Even though she didn’t experience most of it first-hand, my grandmother talks about the things her mother and father lived. During the shoots however, they were comfortable talking about the family story.

When and where can we watch the documentary?

Selim: The documentary will first be screened at the festivals. We’ve already sent it to 22 festivals. We received one approval. We are also taking necessary steps to participate in festivals organized in Turkey. We might have special screenings after the festivals. If we get invited to events, we will gladly screen the film.

Now that the film had its first screening, did your opinions on Ladino change?

Deniz: When we first started the film, for me it was either black or white -whether Ladino would survive or fade away. But, during the shoots in Spain, the ontological meaning of it changed. We started focusing on what it meant to exist. I saw that Ladino language was going to very different places. It does not necessarily mean that we know a lot about a language regardless of it being spoken or not. Ladino has changed. The practice of it has also changed. It is a given fact that after a while, it will no longer be spoken. Now the documenting process of Ladino has started. It will be used in academia; literati will review the language and maybe continue writing about it.

Caglar: In one of her interviews, Karen Sarhon had said that it is a significant success for a language to evolve outside its own homeland and continue to survive for 500 years, each year improving itself. She also added that in this sense Ladino was an exception. We saw this while making the film. We saw that Sephardic culture was open to exploration and renewing itself; we also saw that it constantly adapted to new cultures and improved itself.

Related Newsss ss