Metin Moshe Sarfati and the Albatross

Translation by Janet MITRANI

It was around the end of the year 2017. My search as to strengthen both the writer and the reader quality of the ̃alom Newspaper, which has been going on for 30 years, had struck a ray of light in those days.

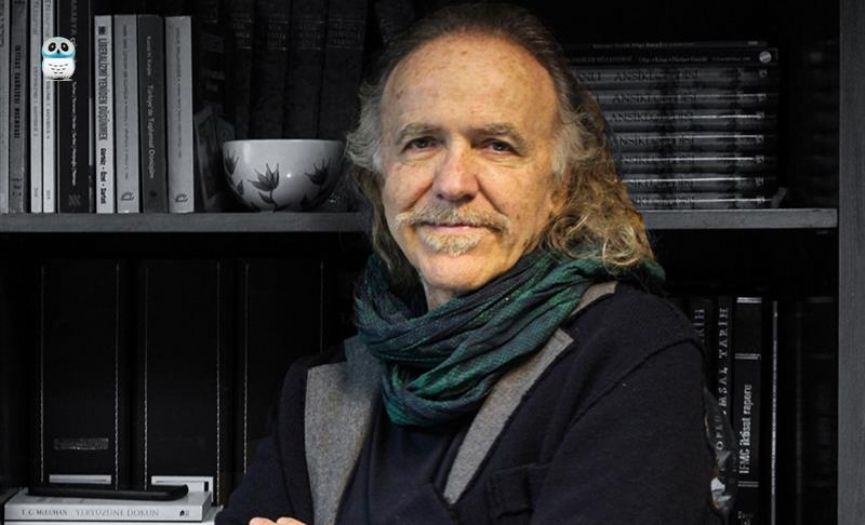

I vaguely remember a message on Twitter saying: "Prof. Dr. Metin Sarfati and Walking with Spinoza in Modern Times". It was selective perception, and twice. As a fan of Spinoza, maybe the most important philosopher of history, and a Turkish Jewish academician whom I had never known - yes, I hadn't known him until that day, seeing them together, a light bulb would go on in my head.

Later I remember my efforts to meet him and a few difficult moments of communication where I requested him to reflect his philosophical and intellectual world to the reader, in the name of watering the Turkish Jewish intellectual life what resembled almost a desert.

He had been very surprised during these consistent periods of invitation. As he had thought that it would be impossible for ̃alom, with the way it was known or perceived, to include his writings.

He was right, because the ̃alom concept in any Turkish intellectual's mind was always like a media outlet that represented the mirror of a conservative and introverted ethnic community.

It was hard to break this perception; since even though ̃alom was in a changing process of reaching the wider community as well, for an outsider what kind of a vision would it have other than acting as this mirror?

However, finally convincing Metin Sarfati, I would feel the happiness of being able to introduce to the society an intellectual who was actually unknown and waiting to be discovered and who had felt like 'the other' not only in Turkey but even in the Turkish Jewish Community, though along hesitations.

There were hesitations, yes, because though Metin Sarfati had enjoyed being called Moshe Sarfati, he had a mindset troubling himself that due to the negative impact of history, the intellectual climate of the Turkish Jewish community was very weak compared to the general society, and that Turkish Jews could not generate their own intellectuals.

If this critical mindset were to be reflected in his writings, what would the 'conservative reader' say, how would they react? How would Spinoza's belief, that the road to virtue was beyond being completely devoted to only the holy and human consciousness would lead him there, would be regarded in a conservative society?

Because Sarfati remembered the history of these lands well. Even after 100 years after the European Jews had their own enlightenment, the Ottoman Jews could not have attained secular education and when in the 1850s the famous banker Abraham Kamondo wanted to open a semi-religious and semi-secular school, some religious Ottoman Jews had performed protests on the streets chanting 'religion is lost', and had attacked Kamondo's house. The struggle to open secular schools had taken exactly 10 years...

Of course, a lot had changed since that day, but the essence of conservatism would always dominate social life. In such an environment how could an intellectual Jew, an intellectual Jew who thought differently than the community, grow up, or even if they did, how much would they be accepted by the community?

Sarfati in his ̃alom articles would say:

"The Jewish Community, which stayed distant from modernity, would be in harmony with the Ottoman-Turkish Community, the wider society they live in, and would not consider taking over their consciousness from the holy! After all, wasn't this the only way they have known for over two thousand years? Judaic life would thus stay dependent on the holy text and its only interpretation. When in the west new styles of Judaism were being discussed with Spinoza, Deutscheer, Buber, a pluralism such as that would not also be possible in these lands.

The Jewish Community being far and deprived of the brilliance of the mind, would not, therefore, be able to realize the contributions their western co-religionists have had in the civilization and the communities they had lived in.

On these lands without Kant, there neither will be Mendelssohn. Then there will neither be Arendt. Kafka would neither see the light of day here."

('The Crisis of a Historical Deficiency' - May 23, 2018)

"...The way of thinking would be inevitably formed around Kabbalah, Zohar, and the Torah in general for centuries; this way the useful people, kneaded with feelings of gratitude and appreciation would in no time gain also the title of citizens.

However, how sad it is that being citizens would not be enough to generate, let alone Spinoza, even a Levinas who had stated, "Everybody should think at least once, philosophize at least once in their lives"..."

('Being a Guest' - May 20, 2022)

"Secularism; on the lands without enlightenment, without Mendelssohn, without Lessing, will only remain like an image such as official day outfits."

('Freud, Post Judaism, etc.' - May 26, 2021)

As can be seen from his articles, among the troubles of being the other, Sarfati was worried about the fact that these lands could not have generated intellectual Jews.

Besides also being concerned about the young generation's not knowing Ladino, he was also ready to pay the price of being eccentric among the society, and in his own words, he had paid it in the final analysis.

♦♦♦

Metin Sarfati would compile his ̃alom articles he had been writing for four years, into a book, just three months before his death. In his work he called 'From the Jewish Human to the Human Jew' and which is almost a book of testament, he has left us the codes of the road from monophony to polyphony in Judaism, as a very valuable legacy.

And finally in his interview with the ̃alom Magazine in May he would say:

"Freedom only grows on the wings of doubt. Suspicion and doubt in the lands we live in do not contain virtue, faith is virtuous. But this, means the acceptance of fate. Fate where consciousness does not blossom in, since it is not of human origin, is not virtuous of course. Because consciousness is what could and should intervene in fate, in the necessity of fate. Virtue, as Baudelaire has said, can be carried on the wings of the albatross in the sky... Only from there can be brought down to earth..."

In his writings, Sarfati always drags the large-winged albatross, the symbol of freedom, after him. Spinoza's albatross had in fact been the guide in his search for freedom.

♦♦♦

Metin Sarfati, the bright child of humanism, tried to explain the unbreakable bond between freedom and virtue, for years, with brilliant words that came from the heart and mind of a real humanist intellectual.

Moshe Sarfati went down in history as someone who has compensated for the intellectual deficiency in this community.

Ones who had reacted to his writings saw that the world did not change with one article. Have they understood that it was futile to be afraid of polyphony, I am not sure...

However, we witness Moshe continue his walk towards the light.

For, the works he has left us and the polyphonic atmosphere he tried to create and explain, will keep on illuminating us.

We do not have to agree with him on everything.

However, we will follow his bright light so that those who fear polyphony do not determine our fate.

Thank you for everything Moshe Metin Sarfati...

Related News