By Benoît Loiseau, Sep 12, 2019 ARTSY

The popular adage “if you build it, they will come,” doesn’t seem to go out of style. Yet ever since Frank Gehry’s much-romanticized

Guggenheim Bilbao opened two decades ago—credited with transforming the post-industrial Basque city into a world-class art destination—not all shiny museums have brought prosperity to overlooked provinces. Take for example Peter Eisenman’s extravagant City of Culture, in Santiago de Compostela, which was never completed due to astronomical costs. And Will Alsop’s arts center The Public, in West Bromwich, England, which was such a fiasco that it was turned into a school in 2013, six years after its criticized opening. So how will the freshly opened Odunpazari Modern Museum (OMM) in Eskişehir, Turkey, make its mark?

Interior view of OMM. Photo by Kengo Kuma and Associates. ©NAARO. Courtesy of the Odunpazari Modern Museum (OMM).

“We want to bring the international art world here,” founder Erol Tabanca told an enthusiastic crowd at the museum’s official opening last weekend in the northwestern Turkish city. “And we want to bring young artists from the region together with international artists.” But when the Turkish construction tycoon started envisioning the project in 2016, he knew it would take more than a white elephant to introduce global modern and contemporary art to this otherwise-understated student town of around 800,000 people. “When you work with a starchitect, that [Bilbao] effect is not guaranteed,” said Tabanca, who is also a trained architect. Instead, he was concerned with orchestrating a meaningful dialogue between a contemporary building and the local context of his native city.

So it comes as no surprise that the visionary businessman enlisted Japanese architect Kengo Kuma—known for his use of natural and sustainable materials—to design the 4,500-square-meter museum. Now home to exhibition spaces, workshops, a café, and a boutique, OMM was conceived as a series of boxes made from stacked timber beams. The design was inspired by the traditional structure of surrounding Ottoman wooden houses, though it also evokes Japanese architecture. It is complemented by OMM Inn, a boutique hotel and restaurant housed within an adjacent refurbished Ottoman-era Odunpazari house.

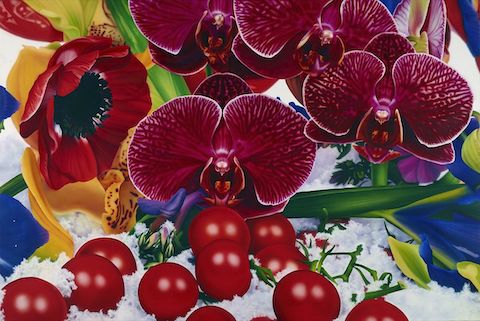

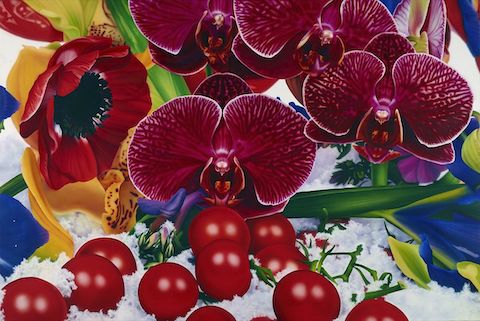

Marc Quinn, Mekong Delta Ice Floes, 2008. Courtesy of the Odunpazari Modern Museum (OMM).

“We’ve tried to translate this kind of intimacy and warmness to a contemporary building,” said the architect, whose award-winning V&A Dundee opened last year in Scotland. Far from the spectacular structures that dominate much of today’s global cultural landscape, OMM’s building is one that favors nature at a human scale. “Modern architecture in the International Style, which was dominated by concrete and steel, severed ties between human beings and their places,” added the architect who, ironically, sourced OMM’s yellow pine from Siberia rather than locally (“very expensive,” he confessed). “This is a landmark as experience,” he added, “not a landmark as form and shape.”

The building is now home to much of Tabanca’s private collection, which consists of some 1,000 works spanning the 1950s to the present day, with an emphasis on Turkish art. Amassed over the past 15 years, it features works by international figures like Hans Op de Beeck,

Marc Quinn, and

Sarah Morris, alongside those of prominent Turkish artists, including

Burhan Doğançay,

Canan Tolon, and

İnci Eviner. Speaking about the origin of his collection, Tabanca noted that he initially bought what he liked, with a particular interest in sculpture. Now, with the establishment of OMM—under the artistic direction of his daughter Idil Tabanca—he said that he will be working with the museum administration to expand the collection.

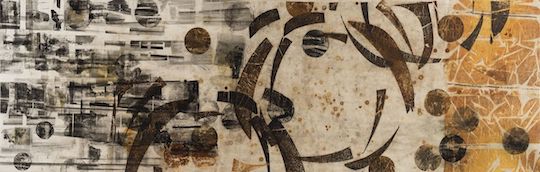

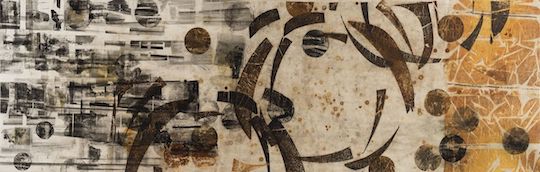

Canan Tolon, İsimsiz, 2015. Courtesy of the Odunpazari Modern Museum (OMM).

The inaugural show, curated by Haldun Dostoğlu, didn’t quite live up to the promise of its astonishing home. Titled “The Union,” the exhibition brings together an underwhelming assemblage of figurative paintings, sculptures, and an odd CGI work, with little aesthetic or thematic connections. Beyond the predictable Jaume Plensa face sculpture by the entrance, only a few of the 60 pieces on show truly stand out. Striking exceptions include Op de Beeck’s sleeping girl (2017), a painting by Turkish artist Neş’e Erdok, and a site-specific installation by Japanese bamboo artist Tanabe Chikuunsai IV.

Interior view of OMM. Photo by Kengo Kuma and Associates. ©NAARO. Courtesy of the Odunpazari Modern Museum (OMM). Courtesy of the Odunpazari Modern Museum (OMM).

View of Tanabe Chikuunsai IV, bamboo installation, at OMM. Photo by Kengo Kuma and Associates. ©NAARO. Courtesy of the Odunpazari Modern Museum (OMM).

Perhaps most compelling, however, was the inclusion of queer artworks—including a homoerotic painting by the German-born, Turkish artist Taner Ceylan; and an embroidered piece by young Turkish artist Erinç Seymen. In a country where Pride parades are repeatedly banned by the authorities, this progressive outlook from the privately owned museum should be celebrated.

Hans Op de Beeck, Sleeping Girl, 2017. Photo by Kayhan Kaygusuz. Courtesy of the Odunpazari Modern Museum (OMM).

Beyond its ambition to put Eskişehir on the global art map, OMM has raised hopes to inspire similar initiatives across the country. “A project of this size, founded by a collector, is a possibility,” said Tabanca, who argues that private collections should be shared with the public. He unabashedly suggested that doing so would also raise the value of his art.

As for Turkey’s artistic community, there are hopes that OMM will help to decentralize the country’s Istanbul-centric cultural scene. “The important thing about this museum is that it is in the middle of the country,” artist Taner Ceylan told me. “This will affect the population, the surrounding cities, it will help empower new artists and voices.”

Benoît Loiseau