Performing for Survival - Cultural Life and Theatre in Terezin - Part II

Part II - Cultural Activities and the Theater

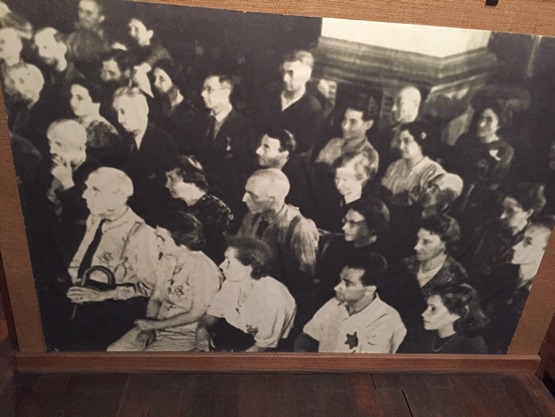

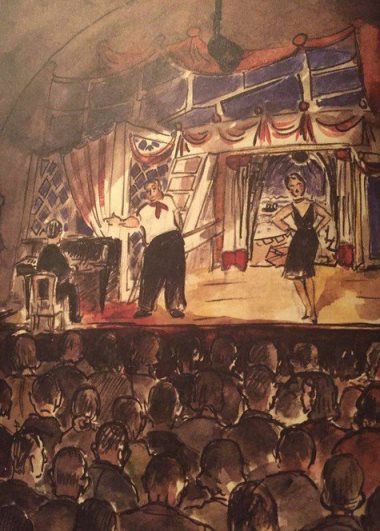

In December 1942, a cafe was opened in the ghetto, where prisoners could enter with a ticket and spend a few hours, as a preparation for the Red Cross Inspection. It soon became a place where prisoners, while sipping their coffees, could see live music performances by other Jewish prisoners like themselves.

Thus, the cultural activities secretly going on in the barracks were transferred to public space. This transformation also led to a change in the performances themselves, which were now more structured, developed in line with the permissions and directions of the Nazis and their plans for propaganda.

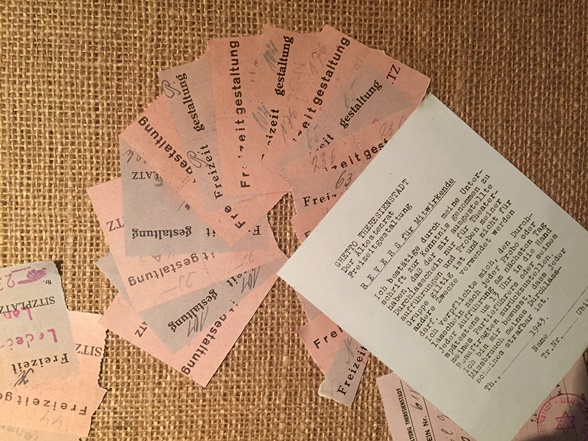

Despite being supported as part of the Nazi propaganda plan, the cultural activities in Terezin never ceased to be activities organized by the prisoners for the prisoners themselves. The program for February 1943 declared by the Freizeitgestaltung can help us understand the dynamism of the cultural life during the camp’s transformation into a model ghetto. The activities in the program can be classified as concerts, operas, and theatrical performances:

-

Concerts: Twenty shows including; religious Jewish music, opera arias, Journey to Lands of Music (premiere), Raphael Schachter Hebrew Chorus (premiere).

-

Operas: In total ten performances including; The Bartered Bride1, Rigoletto (premiere), and The Marriage of Figaro (premiere).

-

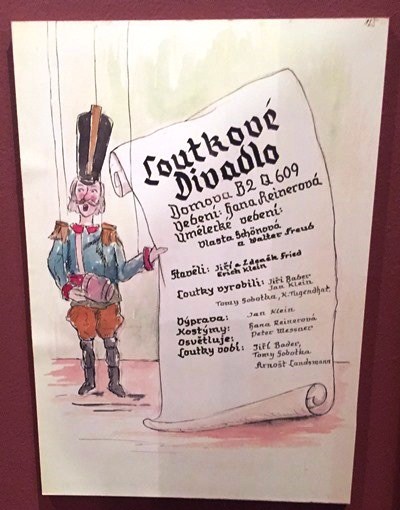

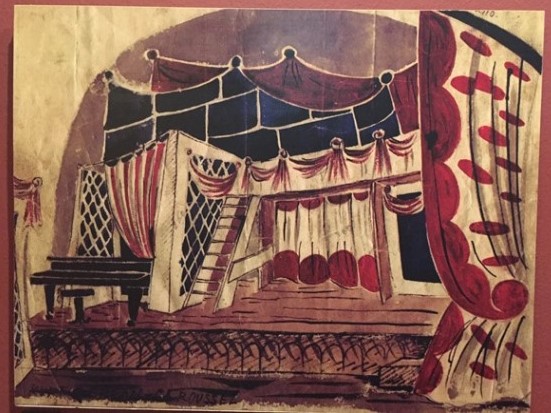

Theatrical Performances: Fifty performances in total including; The Grave (premiere) by Wolker, Youngsters Are Not Admitted (revue – premiere), a cabaret by Stolen Theatre, The Human Voice by Cocteau, Cabaret with Skits by Thoren, songs from The Flower Bouquet by Erben, puppet theatre, and Women’s Dictatorship.2

With a quick look at these plays which were performed on the small stages, it can easily be seen that the Jews in the ghetto had many national, cultural, linguistic and ideological differences. For instance, Jiri Wolker, the Czech author of The Grave, was an avant-garde playwright popular among the communists. Another play, Youngsters Are Not Permitted, was written in German, with slightly obscene humorous elements in its songs and script. While The Bouquet, written by Karel Jaromir Erben, was a classic from the Czech National Revival, The Dictatorship of Women was a three-act comedy written in German in the early 1930s.3

In the following months, there was an increase in the activities according to the list of Freizeitgestaltung: German theatre, Czech theatre, cabarets, opera and chorus performances, instrumental music, foreign language classes, various sports activities such as chess, football and table tennis were also included in the list. In this period, the Freizeitgestaltung had the power of saving the artists from the heavy labour that other prisoners were subjected to and appointing them to positions in art production. They even required that certain artists, though on rare occasions, should not be allowed to leave the ghetto. Among the responsibilities of the Freizeitgestaltung (Office of Leisure Time Activities), were the arrangement of stage areas for rehearsals and performances, the distribution of the tickets and the timely submission of the documents and texts associated with the works of art to the Nazis in order to deal with issues of censorship before artists started working on the scripts.

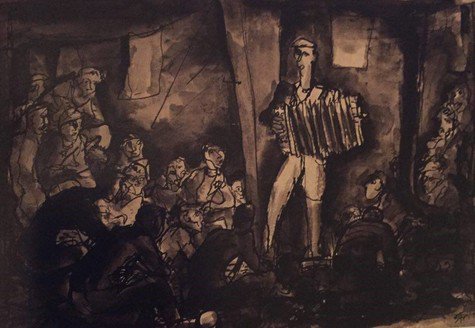

Meanwhile, performances in the barracks also continued to take place along with the official ones. One of the first prisoners sent to the ghetto, Ivan Klima, recounts below how theatre began in Terezin:

“As a young spectator (I was 12 or 13 years old) I experienced several performances in the ghetto. I saw puppet shows and even operas: The Bartered Bride and Krasa’s Brundibar. To this day I recall the strange atmosphere that reigned during those performances: an atmosphere full of excitement, emotion, joy and tears. In Terezin, artists managed to stage several operas and plays. If my memory does not deceive me, the plays that were staged included The Bear by Chekhov, The Marriage my Gogol, and Camel through a Needle’s Eye by Frantisek Langer… In December 1941, my mother and I found ourselves in a living room with 30 women. I remember, how, sometimes in the evening, they sang songs. Sometimes songs by Voskovec and Werich, sometimes folk songs or Jewish songs. As they sang, someone always stood guard in the hallway, to warn the others if an SS officer approached. They sang, even though it was difficult for the women to bring themselves to sing. They sang because it was a demonstration of free life in a hopelessly unfree environment. For the same reason, not long after, theatrical performance and even cabarets were born. (…) It was not possible for us in Terezin to lead the old lives we had left behind, to sustain our old habits and moral values. In Terezin, children would rather die voluntarily than be without their parents. In our new life, where the boundaries between the good and bad were blurred, a rotten potato, or a mouldy piece of bread was priceless.

In addition to artists who painted and drew, there were many actors, directors, singers, musicians and writers in Terezin. Not all could continue to perform their art or create under such difficult circumstances. Some of them could stand the life in the ghetto only for a very short period of time and lost their lives soon after they arrived at the camp without being able to create anything. In addition, not all art that was produced in Terezin survived. It would not be wrong to state that many, or rather, the majority of the texts from that period vanished along with their writers. While reading the texts that reached our day, we should keep in mind the realities of Terezin. If it had only been known then that these texts were being kept, those who kept them would have been sent to Auschwitz or some other camp.” 4

As an actress who went on stage in Terezin, Nava Shan recounts her days in the ghetto in her book as below:

“I remember one of the first evenings in the camp. We were sitting in a crowded room on the muddy, bare floor. When people realized that I was an actress they requested that I "act something". I gladly complied. I knew entire poems, parts of plays and tens of monologues by heart and that's how I started to circulate, in the evenings after work, between the barracks and blocks. During working hours, I only thought of what program to give in the evening, memorizing the texts in my head.”5

In the group of theatrical performances, I call the texts written in Czech and German, Terezin Plays. One of the texts in Czech is titled Radio Show, a composition of radio programs broadcasted on Prague 1 before the war. Written by Felix Prokes, Vitezslav Horpatzky, Pavel Stransky, and Kurt Egerer, the play has a fragmented structure resembling a radio broadcast, consisting of short comedies, folk songs, news, educational programs with themes such as morning recreations, agriculture, as well as folk songs, hymns, story time and sports. In addition to Radio Show, which is full of elements reminiscent of pre-war times, another play that draws attention with its time-space construct is a revue titled Prince Bettliegend, a satirical fairy tale written by Frantisek Kowanitz about a person skipping work as he was prescribed bed rest due to illness. With many songs, the play’s fantastical construct of time and space does not match with the reality of the Terezin camp. The first scene takes place in a wizard’s workshop. The wizard inadvertently casts a spell on the prince, who, as a result, cannot move. The wizard’s assistants Hocus and Pocus decide to rescue the prince. Beginning as puppet theatre, the play ends with the Prince stating that he officially has the right to lie down as bedridden and so he does. Being bedridden is “a happy ending” for the play as well as for Terezin, where it is indeed a happy ending in the reality of a concentration camp to be able to lie down even in the narrow bunk beds crammed with people.

Written by Zdenek Elias and Jiri Stein, The Smoke of Home tells the story of four men imprisoned during the Thirty Years War, which had started because of a religious conflict between Protestants and Catholics and cost the lives of one third of the Czech population. Although relevant to the Terezin camp with its theme of war and religious difference aspect, the play was never staged in the ghetto. According to Holocaust survivors’ testimonials, the play was not written to be performed in Terezin, but life in the ghetto had been depicted in its text. The play, which was recited secretly as a closet drama in the barracks, is striking in the fact that it reflects life in Terezin through the reality of another old war.

Another play composed by the writers of Radio Show, namely Felix Prokes, Vitezlav Horpatzky, Pavel Weisskopf, and Pavel Stransky is Laugh with Us, a cabaret which takes place in the post-war future as opposed to Radio Show’s pre-war times. In the play, a group of friends who return to Prague after their time in Terezin, look back on their lives in the camp from a safe distance. Life in the camp is treated lightly with a powerful sense of humour, rendering the play, as if it were, “a joyful resistance”.

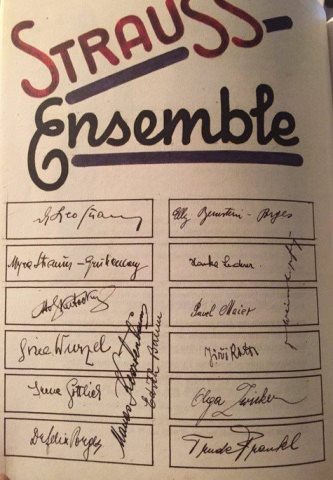

The most famous of the German plays written in Terezin is, From the Strauss Cabaret by Leo Strauss and Myra Strauss-Gruhenberg. The play includes joyful, funny songs and sonnets. While a poem about the crowded conditions of the ghetto might include realistic lines such as “we are buried here alive”, the rest of the play does not present an immediate link to the daily life in the ghetto. Events take place in Vienna in the decade before the war. In an effort to recreate the atmosphere of the period, the play consists of sections titled Spa Music, Marriage Dialogue and Pierre Puts Everything in Order as well as songs about ghetto reality, such as Terezin Tango and Waltz in Terezin.

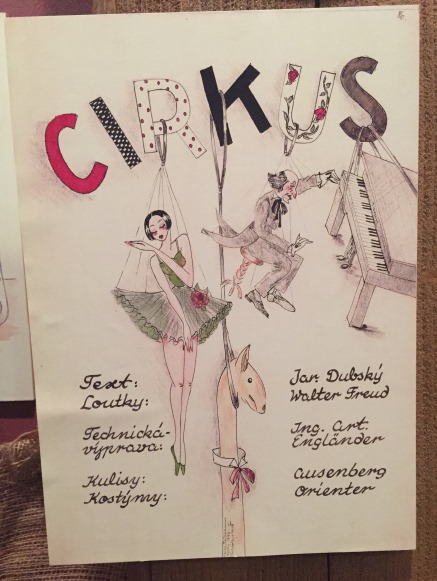

A play written in German is The Treasure, a puppet theatre penned by Arthur Englander. In the play, two children and a clown accompanying them travel to Africa in search of a treasure. On their journey, they live with an Arabic-speaking tribe and return home with a treasure that can save even the poorest who is at the verge of death because of hunger: Potato. The rest of the play presents differences because of two existing scripts. While in one the play ends with an announcement that the same story will continue in a second puppet play, in the other, the clown becomes the king and gives treats to everyone including the children and the elderly. Taking place in a fantastical time and space, the play ends happily in both versions.

Another play that includes fantastical elements is The Death of Orpheus, written by Georg Kafka, who was a distant relative of Franz Kafka. Regarded highly by the residents of Terezin due to this relationship, during his days in the camp, Georg Kafka wrote many poems, stories, fairy tales, and scripts for the stage which were translated into German in the ghetto. Like the previous plays mentioned, The Death of Orpheus also contains references to mythological stories which do not match with the reality of Terezin. The scene with Orpheus and his mother is an example to such references. In his play, Kafka subtly asks questions that his audience, the prisoners in the camp, might be facing, such as, “how ready are we to sacrifice ourselves for our loved ones?”, or “is it possible to find peace in embracing death?”

Written by Hans Hofer, From the Hofer Cabaret presents ironic exaggerations, but at the same time accurate descriptions of the life conditions in the ghetto. Hofer’s writing is brave and powerful, addressing such issues as bribery and favouritism. The themes regarding the ghetto life are set in familiar melodies from Vienna, thus offering brief nostalgic moments to his German-speaking audience. The cabaret brings together in a humorous style the bureaucracy of the ghetto and the pre-war lives of the prisoners.

As with all works of art, the Terezin plays were also created out of an aesthetic concern. However, the plays are also inscribed with an existential meaning in the author’s will to survive, which best manifests itself in the time and space construct of the plays. Inclining towards the nostalgic, most of the plays take place in the pre-war period, but in a time in where it is possible to keep the memories of the life before camp alive, as well as holding on to the hope of a new life after the war. As recently discovered, the Terezin plays are textual evidences of the struggle for life that thousands of men and women in the camp gave by trying to hold onto both the past and the future through art.

With respect for their memory...

1. The Bartered Bride, overture: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QLUm_yvnyo4

2. Bondy, Elder of the Jews, Grove Press, New York 1989, p.365.

3. Lisa Peschel, Performing Captivity, Performing Escape: Cabarets and Plays from the Terezin/ Theresienstadt Ghetto, Seagull Books, Calcutta, 2014, p. 31.

4. L. Peschel, ibid., pp. 36-38.

Related Newsss ss