"Israelis Found ´The Pageant´ Shocking"

´The Pageant´, the documentary which previously met with the audience in the most famous festivals of the world, was screened as part of the Istanbul Film Festival.

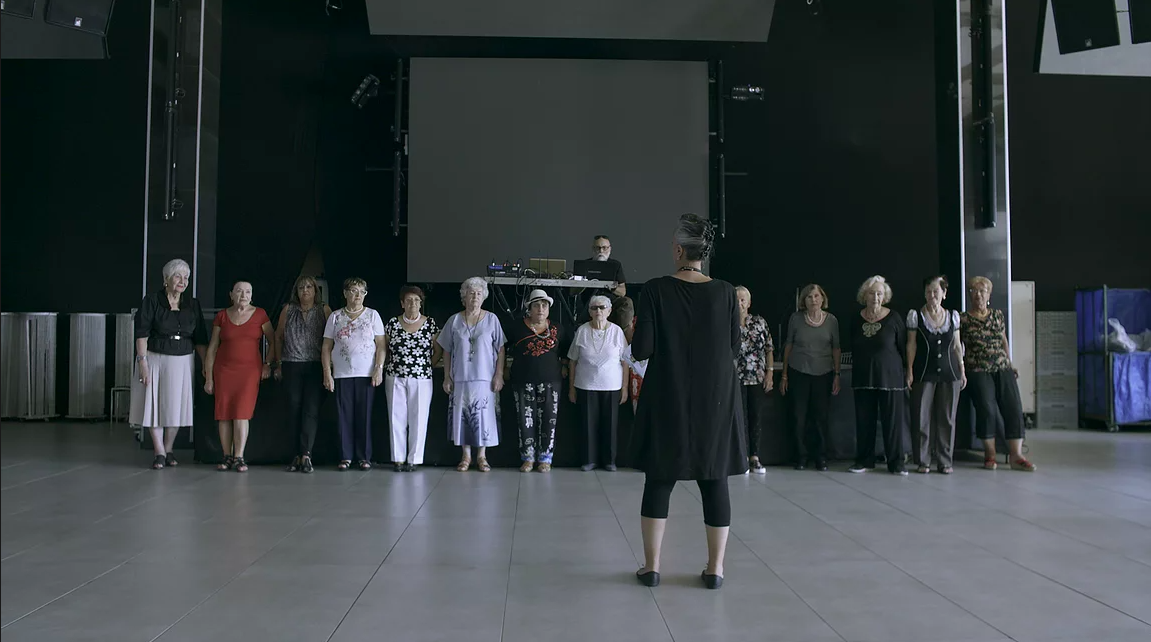

Translation by Ekin GIDON

'The Pageant', the documentary which previously met with the audience in the most famous festivals of the world, was screened as part of the Istanbul Film Festival. The production featuring an annual beauty pageant that has taken place since 2011 in Haifa between women who survived genocide under the Nazis, discusses how collective memory timing out turned things into a political show. We talked with the director of 'The Pageant' Eytan Ipeker and producer Yoel Meranda about harsh and shocking documentaries, the new generation’s connection with the past, and the Holocaust, along with the opinion on festival films in Turkey and their new projects.

'The Pageant' was screened at the Istanbul Film Festival. The Turkish premiere however took place during Antalya Golden Orange Film Festival. Can you explain the process in which this idea has come to life? What was the event that inspired you and get you started?

Eytan: When I was younger, I was always a part of Holocaust remembrance events. There was always one question that came up: “What can we do this year that will surprise people?”. It was almost as if there was always a need to up the theatricals. For a long time, I was thinking about the ethical limitations of such events. About four years ago, I came across an article written about the contest on the website of the Haaretz newspaper. The pictures accompanying the article were startling. I didn’t know how to feel: a deeply problematic and superficial organization such as a beauty pageant combining with the traumatic fact of genocide made me think for a long time. Finally, I told myself, “Since you’re thinking about this topic so much, go and face it upfront." I found out about a Christian Evangelist establishment supporting the right-wing policies of Israel sponsoring the event later, while I was researching. This took the project to another dimension. Witnessing moments such as the issuing of numbers yet again to women who have escaped genocide, Sara Netanyahu interrupting a constant’s sentence for a VIP entrance to the hall and the judges giving extra points for those who had survived Auschwitz was immensely unsettling for me.

This was a joint project by Turkey-France-Israel-Germany. How did you manage to find common ground between four countries, was it difficult?

Yoel: It was a step by step process. First of all, since we were going to shoot the film in Haifa, we needed an Israeli partner. Spiro Films is one of Israel’s youngest and bravest studios. When we contacted them they had newly received the Golden Bear Award in Venice for their new film 'Foxtrot'. We were afraid of our idea being stolen, but we found the security and pragmatism we were looking for in Spiro Films. Later when we needed cash, Welt Film from Germany decided to invest in the project. At last, Carine Chichkowsky joined the project as a co-producer. The biggest financial support for the film was provided through her.

The film’s world premiere was done at the Vision du Réel Film Festival, one of Europe’s most important documentary festivals. After, you also met with the audience in international festivals such as Sarajevo and Odessa. What kind of reactions are you receiving?

Eytan: We tried to make a film that doesn’t look down upon Holocaust survivors that enter the contest but still bring up questions about the contest itself. Looking at the reviews about the film, it’s nice that this was understood. Other than that, I received commentary such as, “The criticisms aren't clear enough”, while some said, “Your film is very harsh”. This ambiguity is actually something I like. It’s also a bit about where the viewer looks at it from. For example, almost all the Israeli people I showed the film too found it very jarring. The panel that was organized after the viewing at Lugano Human Rights Film Festival featuring the concept “Genocide, Pain and Spectacle” made me very happy.

Yoel: For example, there were great reviews on Le Monde of France and Filmmakers Magazine of USA. Distribution will be done by Grasshopper film studio, which gained a name for itself by distributing successful art films such as Locarno winning “Vitalina Varela” in North America a short time ago. In any case, the festivals you mentioned picking the film are positives on their own.

"It is very important for me to face a contest where pains are being competed"

The documentary is about an annual beauty pageant done since 2011 in Haifa among women who survived genocide under the Nazi regime. The introduction also has the expressions “In ‘The Pageant’ director Eytan İpeker explores the story of Sophie Leibowitz who has attended the contest since 2016 and discusses how collective memory timing out turned things into a political show”. In your opinion must all works made in the name of cinema have a social message? What are you explaining to the audience with this production?

Eytan: I don’t think an artistic work must be socially concerned. I wanted this film to have an open ending, a side that takes the audience and leaves them. I need to face a contest in which pains are being competed, the flames of nationalist emotions are fanned, and the women who couldn’t win are sent away with beauty cream. On the other hand, you must understand what this organization means to women like Sophie who compete for very personal reasons. I aimed to make a film that didn’t readily judge for the audience and contained these kinds of contradictions.

Do you think the new generations are conscious enough about the Holocaust? How can we succeed in not losing collective memory?

Eytan: In time the Holocaust has started to be remembered by cliches and this is very problematic. We use the phrase "Never again" like we are still in 1946. Many pains have been lived from that day until now. The reason why the younger generation perceives the Holocaust as something of the past is partly because of this. For interpreting the Holocaust from the perspective of today, books such as 'The Holocaust and Collective Memory' (Peter Novick), 'Eichmann in Jerusalem' (Hannah Arendt), and 'Modernity and the Holocaust' (Zygmunt Baumann) were very significant to me. I would also like to add this: I find the use of pain and anguish of the past to support nationalistic narratives very dangerous. To remember the past like this may desensitize us to the pains of others. We must at least be aware of this danger.

"Sometimes as a producer, I bring a dose of coolness to the environment"

Together you create many works that will leave a mark on people’s minds. Do you criticize each other, where do you disagree the most?

Yoel: The connection Eytan establishes with his projects are very personal, thus very passionate. I can say that as a producer, sometimes I feel the need to bring the environment a dose of coolness. It must be said that the director/producer relationships inevitably create friction: While the director tries to portray what comes from the deepest part of their soul on the screen, the producer is the person who is responsible for reflecting the clash between the realities of the sector and their dream. Every so often, as a producer, you find yourself as the person who represents all the ugliness in the universe. Believe me, this position sometimes hurts my heart as well.

Eytan: Yoel is an extremely creative producer. He dreams along with the director for the project to be good and puts his own ideas on the table. Since I trust his eye for aesthetics, I look at my ideas that haven’t been filtered by him with doubt. This process, however, requires a lot of discussion, and sometimes things heat up: we both have excitable personalities. There is also this: Any decision made about the budget is also a creative decision. For example, shooting with a good director of cinematography for five days or shooting with our own camera for fifteen? Consequently, I find myself in a lot of arguments about the budget.

Usually, you prefer doing projects about people who have a story to tell or projects that are informative. Will we one day see you in the world of popular culture or a box office movie?

Eytan: Why not? I don’t personally give any importance to this kind of distinctions.

Yoel: I think we must examine cultural/economic changes that not only separated art and box office movies so far apart but also tore down the middle. In the history of cinema, there are many eras of high art and box office intersect like 1950’s Hollywood, and there is no rule that says this divide must continue. So yes, someday maybe there will such an idea that artistic urges will align with box office necessities, why not? However, I can’t see myself making a box office movie that doesn’t satisfy me artistically. I don’t even know what works and doesn’t anyway.

“In Turkey, festival films are perceived as somber"

What do you think about the audience of festival films in Turkey being a specific crowd and a lot of these films not being able to find what they were looking for in the box office? What kind of path must be followed to change this?

Yoel: There is a perception that festival films are somber. However, a lot of films we watch at festivals are filled with humor. Other than that, I don’t think the problem you are talking about has one solution. From giving cinema education from school, film libraries being opened to get people to love the art of cinema from a young age to festivals being supported more financially. Though first, the people with authority in our society must see that art isn’t a luxury but a necessity for societies to remain alive in the long run. A society without new expressions and developments unavoidably grows rotten and collapses inwards.

The film 'Album' you produced received the France 4 Visionary Award from the 2016 Cannes Film Festival’s International Critics’ Week. What is your biggest dream concerning cinema? For example, have you ever fantasized about receiving a Palme d’Or award? How valuable are awards to you?

Eytan: Awards and festivals are very important for my career. Also, it’s very enjoyable to feel understood. Even so, the bond I have with cinema is a lot more personal. As long as there are projects that interest and excite me, I’m content with my life.

Yoel: Of course, one feels delighted to be esteemed for the work they have done. Moreover, when the opposite happens you can lose your motivation. Although to be honest, in my opinion, there isn’t much value to it in the long run either. I think awards represent their era’s institutionalized artistic perception. Directors who create new cinematic languages naturally clash with these perceptions.

“I kept a video diary during the pandemic"

How was your creation/production process during the pandemic? What are your new projects?

Eytan: I spent a significant amount of this year working on my documentary. Recently I’ve been working as the film editor of a new documentary project in Germany: it will be completed this year.

Yoel: Right now I’m developing two of my own feature-lengths. One of them is a documentary I shot in South Africa, for that we are at the seeking financial support stage with my French producer. The other one is a Balzac adaptation I plan on shooting in Paris. The pandemic was a creative period for me, for example, I kept a video diary. It both helped me emotionally manage that difficult period, and since it was a personal project, created a space for me to think about cinema freely.

“I want to do projects about the Turkish Jewish Community"

If you were to make a film about Turkish stories and these lands, what topic would you like to work on? From Turkish directors, what are the names of some of your favorites?

Yoel: From Turkish directors barring the ones I worked as producer for, some of my favorites are; Belmin Söylemez, Tayfun Pirselimoğlu, Zeynep Güzel, Melisa Önel, Mahmut Fazıl Coşkun, Yasemin Akıncı, Ekrem Serdar, and the late Seyfi Teoman, who we unfortunately lost too soon. I would also like to step out of the role of directors and remember legendary film editor Ayhan Ergürsel who we lost last year.

Eytan: From old school directors Ömer Kavur has always been a great source of inspiration to me. I hope I can do other projects in Turkey. I would say I want to do more projects set in the Turkish Jewish Community because it’s a community I’m deeply familiar with.

Despite your young age, you have made solid steps in your international careers. What advice can you give to young movie makers to survive in this sector?

Yoel: I suggest for them to create their own communities and cinematical families. If the actors or directors are worked with didn’t trust me, I couldn’t do a quarter of the things I’ve done till now.

Eytan: I agree word for word with Yoel. Also being in feature-length movie sets is a great environment to observe the production process and getting to know film professionals closely.

Related News