Performing for Survival - Cultural Life and the Theatre in Terezin - Part I

Part I - Setting up of Terezin as a Concentration Camp

Nazi concentration camps are places where nobody wants to enter voluntarily and be subjected to the bodily experience of being in a concentration camp, but once inside, no one can even mentally leave easily, either. Researchers have been attracted by the weighty, never-ending questioning that imprisoners go through in the camp whereby one encounters the darkest sides of one’s self. Recent research on the Holocaust has revealed documents with detailed information on the daily lives of the Jewish prisoners in Nazi concentration camps. We have thus been able to witness the depth of the existential resistance displayed by the Jews under direst conditions in the camps. A considerable amount of the evidence which we can trace the resistance I am referring to, comprises the works of art produced by the Jewish prisoners during their time in the concentration camps, ranging from theatre, music, literature to various other forms of art. Sadly, unlike their work, none of the artists survived.

Until recently, the only art activities known to have existed in the concentration camps were the Women’s Orchestras, which were established by the order of the Nazis in the Auschwitz and Birkenau camps. The orchestras were initially founded in order to provide marching music for the Jewish prisoners as they walked from the barracks to their work stations and back. Their melodies accompanied the prisoners on every step on their way to death. We now know that the production of art in the Nazi camps was in fact independent of Nazi orders, secretly governed by the Jewish people themselves.

The concentration camp where art production was most intensively carried out was the one in Terezin, where talented and well-educated Jewish artists from Central Europe had been forced to come together in a town a few kilometres away from Prague. This article will focus on the theatrical performances produced in Terezin concentration camp.

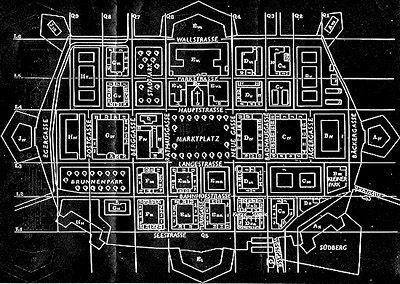

Terezin had been designed as a garrison town, whose construction was completed in 1784. Contained within high walls, it was indeed like a ghetto. It had been home to Christian Czech citizens from the time it was built until its transformation into a Nazi concentration camp, which began with the construction of barracks. This period is called the foundation period of the camp.

The cultural activities in Terezin, that had mainly consisted of improvised sketches, poetry reading and singing in the barracks, started taking place within the first six months of the camp’s construction. These activities were organised even after a few days of arrival of the first prisoners. The leaders of the Jewish community made an application to the Nazi administration arguing that the struggle of the Jews in the camp who were now forced to live as prisoners to hold on to life through art should not constitute a crime, and asked the administration’s permission to organise cultural activities. The Nazis granted permission to the people who they knew were going to die soon. In the Daily Orders issued on December 28th, 1941, it was announced that a “friendship evening” would be organised. Due to the considerable increase in the number and quality of the cultural events in the ghetto over the next two months, in February 1942, the Jewish leaders decided to set up an administrative unit for their organisation, within the prisoners. Thus, Freizeitgestaltung (Office of Leisure Time Activities), which would play a significant role in the cultural life of the camp was formed, directed by a young rabbi, Erich Weiner. With the establishment of this unit, the foundation period of the Terezin ghetto was completed.

The second period is the transformation of Terezin into a “model camp,” which began with the completion of the local Christians’ transportation from the camp. As soon as the last Christian exited the camp, the Nazi administration opened the doors of the barracks. The prisoners were allowed to walk freely in the camp, but they were banned from the buildings and areas used by the SS.

In this period, although men and women continued to live in separate barracks, they were allowed to see each other during their time spent outside. All children lived separately from their parents, staying in the barracks reserved for children. The children’s caregivers organised various cultural activities including singing songs and playing games for children, who were unable to receive any formal education under current circumstances.

In the summer of 1942, Jews from other countries speaking different languages arrived at the camp. Arriving on June 2, 1942, the first of these groups were from Berlin, followed in the next months by many other groups of Jews brought from various German cities. The new transfers led to a change in the demographic structure of the ghetto, particularly in terms of nationality and age. The German Jews who came later were older than the Czech Jews, the ghetto’s first residents. They had been told that the Terezin was a town with thermal springs and that if they donated their property to the state, they would be able to live the rest of their lives comfortably in Terezin. Almost all of the Austrian Jews were brought to Terezin within four months. Between June 21st and October 10th, 1942, the number of Austrian Jews who were brought to the camp was 14,000. Their average age was 69 years. Unprepared for the reality in Terezin which was nothing like what they had been promised, elderly German and Austrian citizens began to die due to hunger, illness and exhaustion, leading to a rise in the death rate in the ghetto. In September of 1942 alone, the number of deaths recorded in the ghetto was 4,000. The camp had now reached its highest population of 60,000 and the mortality rate was almost 10 people per day. By the end of 1942, with the increased mortality rate and some of the prisoners having been sent to other concentration camps, the population of the ghetto had dropped to 40,000.

The ghetto was relatively calm at the end of 1942, which marked the beginning of a new period. No new barracks were being constructed for the new arrivals, who settled in the houses previously occupied by civilians. Nevertheless, life conditions were still utterly strenuous. The prisoners were not allowed to own anything apart from the wooden bed they slept on and a few personal belongings on a shelf. They didn’t have any privacy, either. Food was prepared by the respected elderly members of the ghetto, cooked in a few kitchen areas and portioned out to the prisoners on the basis of their age and the work they do in the camp. The young prisoners who worked outside were given more food than the others. Water shortage was one of the greatest problems. Designed for a population of 10,000 people, the water infrastructure was not sufficient for the ghetto which hosted five times as many people. Bathing was based on a ticketing system. In such an environment where even minimum hygiene was not possible, contagious diseases had become rampant, further increased by infestations of lice, fleas and bedbugs.

The national variety in the population of the ghetto increased with the transportation of the Jews from Denmark and the Netherlands in 1943. Due to various clashes between the newcomers and the first residents of the ghetto, the Nazis appointed leaders from the Jewish community, who were allowed to settle in houses with relatively more comfortable life conditions. They were also given less responsibilities and provided with protective health services. Although the majority of the prisoners were aware that the Nazis consciously created the national distinctions and class differences within the Jews, they could not prevent the tension among the camp prisoners. Therefore, a court was set up in order to resolve the conflicts that arose.

While the tension among Jews was increasingly gaining ground, a new development led to a significant step taken towards rendering Terezin a model ghetto. In November 1942, the Nazi administration granted a request by the International Committee of the Red Cross to carry out an inspection in the Nazi concentration camps and Terezin was chosen as the suitable camp for this visit. This was immediately followed by a request by the Danish authorities for a similar inspection, in January 1943, as 446 Jewish citizens of Denmark had been transported to Terezin. The Nazis made elaborate plans with the sheer purpose of concealing the reality of the concentration camps. Upon the approval of the authorities in Berlin, the “beautification” process began, preparing Terezin for its role as the secluded Jewish settlement that had initially been promised to the prisoners.

The preparations paved the way to a new period during which the cultural life in the ghetto flourished. Terezin was beautified as if it weren’t the same place where 4,000 people had lost their lives just a few months back. As a result, life in the ghetto during the period between November 1942 and December 1944 proceeded along two lines: the fictional one prepared for the awaited visitors against the harsh day-to-day reality of the ghetto. Masking began with the opening of shops that have quite a limited variety of goods in the ghetto, with the aim of making it look less like a prison.

Before the inspection of the Red Cross scheduled for December 1943, another important step was taken towards making Terezin a model ghetto: A new order to set up the Stadtverschonerung, the beautification office, was released. By the spring of 1944, the renovation works in Terezin were almost completed thanks to the hard labour of prisoners. The long-waited visit of the commission consisting of one Swedish and two Danish inspectors, took place on June 23rd, 1944. The commission was accompanied by a Nazi officer, a few officials from the German Red Cross, and authorities from the Reich Ministry of Foreign Affairs.

The visitors began their inspection following a predetermined itinerary. Their first stops were the bakery, bank and the performance of Brundibar, the children’s opera. Despite having serious doubts about the quality of living conditions in the ghetto before their arrival, the members of the commission were impressed by what they saw in Terezin and wrote a positive report approving the conditions in the camp. The Swedish member of the commission, Dr. M. Rossel had later stated in his official report that he had been amazed by what he had seen, adding that everything had been clear as daylight and that nothing could have been hidden from them.1

Following the success of the inspection, the Nazis decided to make a documentary about the ghetto, for which the well-known German-Jewish actor and film-maker Kurt Gerron was appointed as the director. Titled “An Idyllic Concentration Camp: Terezin: A Documentary” (Das Konsentrationslager als Idylle: Theresienstadt: Ein Dokumentar Film), the documentary was shot in August and September 1944, capturing the last images of many prisoners before they were sent to their death.

Related Newsss ss